Since the start of the MCU in 2008, we’ve seen three different live-action Batmen across three different universes in five different movies. But it’s that “different” that is key. While the MCU imposes a house style for the entirety of their output, Batman has had (at least) three tonally, aesthetically, and thematically distinct forms in cinema since the birth of the biggest franchise ever.

That’s to say nothing of the iterations that came before, which each offered visions of the dark knight that are as different from one another as they are from what we’ve seen in the 21st century. Based on this diverse cinematic history in live-action and the character’s many iterations in comics and animated movies, I’d like to make the argument that there can indeed never be too many Batman movies.

While there are debates broadly about whether “superhero fatigue” is real or a myth, it seems increasingly likely that there is universe fatigue, as it becomes increasingly common that to see the next movie in a major franchise, you have to be sure you’ve completed your homework on the last however many entries and maybe a spinoff or two. The Batman movies released over the last decade and a half haven’t entirely avoided this, especially as DC rushed to create an interconnected universe to rival the MCU, but a disillusionment with the homework-driven model of entertainment helps make a strong case for more individual outings from the superheroes that we want to see on screen. And no other hero is more malleable than Batman.

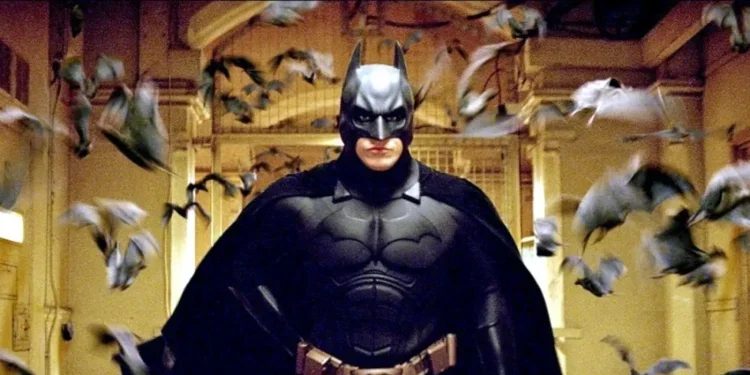

From Christopher Nolan’s grounded, crime drama realism which offered a Joker that many believe is a veteran of the wars in Iraq or Afghanistan, to Zack Snyder’s highly stylized DC universe that saw the dark knight face off against a giant alien in his first outing and a literal god in his second, and now Matt Reeves’s world, that’s so dark (literally) that it’s reminiscent of Robert Rodriguez’s ‘Sin City,’ offers a detective epic that draws from serial killer movies.

But it’s not just the visual style or the types of stories they inhabit that are distinct; the Batmen themselves differ greatly. Throughout the ‘Dark Knight’ movie trilogy, Christian Bale struggles with whether or not there should be a Batman. Ben Affleck has been hardened by his years as the vigilante and sees everything as a threat, but over the course of the Snyder films, he grows into a man with great faith and hope. And Robert Pattinson’s Bruce Wayne uses Batman as a shield to avoid being Bruce Wayne, even if he doesn’t quite understand how best to be Batman.

Beyond these major aspects of characterization for Batman as Batman, there are also contrasts in the way these men exist in smaller, more human ways, for instance, when it comes to romance. We see Bale’s Bruce Wayne with models and ballerinas but also see him have real romantic connections with Rachel and Selina. While Affleck and Gal Gadot’s Wonder Woman are clearly attracted to one another, and there’s been significant discussion of whether or not Battinson has ever had a romantic (nevermind sexual) relationship at all. These are wholly different men who have entirely different ways of navigating the world just as men, to say nothing of the way they function as superheroes.

They are, of course, very different kinds of heroes too, whose battles emphasize the major thematic differences of their creatives’ concerns. Nolan’s concerns are all too real but also overwhelmingly social. ‘Batman Begins’ examines the way fear immobilizes a populace through Batman’s fight against the mob and Scarecrow. ‘The Dark Knight’ is interested in how people respond to chaos and how strong the bonds and mores of society truly are when we are threatened.

‘The Dark Knight Rises’ may have bitten off a bit more than it could chew with its ambitious response to the Occupy Wall Street movement. Snyder’s interests are theological as he introduces a Batman who has lost his faith in anything but his own power to bend the world to his will and shows us his transformation into a man who tells Alfred to be more optimistic. And Reeves seems most interested in what Batman means to Batman, as we see Pattinson hide behind the cowl as a symbol of fear before realizing that he must, in fact, be a symbol of hope, not only for Gotham but for himself.

All this, though, is only a part of the story. And while it’s certainly important to emphasize that there are already a wide variety of live-action Batman stories that we’ve seen onscreen in just the years since the start of the MCU, the real case for why there can never be too many Batman movies comes from the comics, and increasingly the animated movies as well. There have been a huge number of different Batman stories over the course of the character’s 80-year career, of course, but what’s more interesting is the current boom of one-off Batman stories. While there have been alternate universe stories for decades, more recently, DC’s Black Label has exploded the number of creator-driven, self-contained stories in the DC output, many of which focus on Batman.

While the Black Label stories are, unsurprisingly, dark and more adult-oriented, it can’t be denied that even within that tone, the Batman books from the sublabel have expanded the way we see the dark knight and his adversaries. For one thing, ‘Batman: Damned,’ the first story from the sublabel, showed Batman’s penis.

The success of Sean Murphy’s ‘Batman: White Knight,’ which imagines a reformed Joker who labels Batman as the real villain of the city due to his mass property destruction and extralegal violence, birthed a mini-universe that’s been unofficially titled the “Murphyverse.” And along with allowing celebrated comics authors like Scott Snyder, Tom King, and Jeff Lemire the opportunities to write Batman stories unencumbered by any concerns for canon, Black Label has also allowed beloved artist Jock his first outing as a writer.

But comics aren’t the only medium where Batman stories are proliferating. Along with ‘The Dark Knight’ and ‘Iron Man,’ 2008 saw the release of ‘Batman: Gotham Knight,’ an anime anthology movie that ostensibly exists in the same world as Nolan’s films but has almost no connection to those movies and instead offers six distinct tales of the caped crusader, each in a different animation style. Since then, we’ve seen a number of adaptations of self-contained Batman comics stories to animation with varying degrees of success (looking at you, ‘The Killing Joke’), as well as original animated movies that draw on a variety of inspirations, including anime and 1970s kung fu films.

After the distinct cinematic visions of Nolan, Snyder, and Reeves, as well as the pastel cloth donned by Adam West and Burt Ward, the gothic art-deco of Tim Burton, and the “toyetic” excess of Joel Schumacher, why do we still see arguments that there should be less Batman movies? The complaint that these films are all similar and covering similar ground rings all too hollow when we consider the variety of movies that exist. While some think that there’s simply too much Batman in all mediums, it’s not without cause; obviously, there’s the financial aspect, but the character himself is so malleable that it’s possible to tell hugely different stories about the character.

I’m not arguing that there should be more Batman movies (though personally, I’d love more and smaller films that run less than two hours), simply that the complaints of “too many” don’t hold up to scrutiny. Whether we consider the existing live-action films or the massive variety of stories that exist and continue to be produced in comics and animation, it’s clear that there are entire cinematic worlds yet to be explored with Batman.