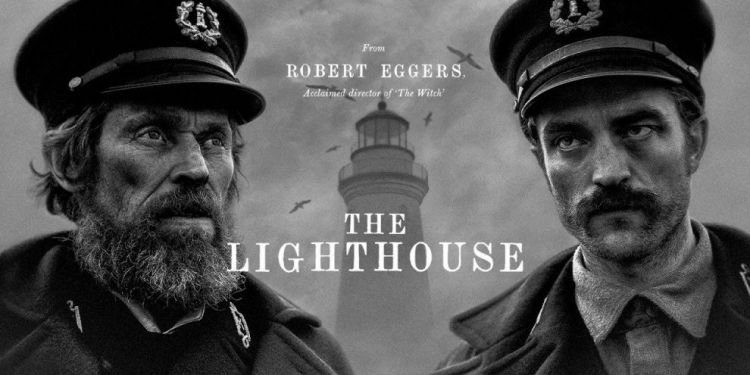

With 2015’s The Witch, director Robert Eggers made his debut with a period piece about a family in the 17th century that moves away from civilization and begins to fall prey to a group of witches that may or may not exist. With his second film, Eggers proves that he has a propensity for making films that take place in historical New England and involve isolated people who have to deal with an ambiguous threat. The Lighthouse, written by Robert Eggers and his brother Max Eggers, also borrows from letters and sources from the period, this time the late 19th century, in order to promote a feeling of authenticity.

I have to confess that I had a lot of issues with The Witch. I found it slow, uneventful, and difficult to understand at times, in both sense of trying to grasp what was happening and in trying to decipher what the actors were saying. Many will likely have the same issues with The Lighthouse. But what sets The Lighthouse apart is its palpable dread. There’s always a sense that one of the characters could explode at the other at any moment, that a horrible calamity could occur, or that the film is building to some great and terrifying revelation.

The Lighthouse tells the story of two men who arrive on a remote island somewhere off the coast of New England to tend to the lighthouse for a month. Winslow (Robert Pattinson), the younger of the two, has never worked a lighthouse job before, and it’s clear that he’s trying to escape something from his past. Butting heads with him is Wake (Willem Dafoe), a veteran lighthouse keeper who guards the light itself jealously. He won’t let Winslow tend to it, instead giving him every menial task under the sun to carry out, while berating him as he goes about them. Naturally, they’re a bit of an odd couple, to say the least. Winslow constantly gets into fights with a territorial seagull, who may or may not possess the soul of the former keeper who died under mysterious circumstances. He also hallucinates various goings-on, which include a mermaid washing up on shore and a giant tentacled beast in the lighthouse. And yet, he seems the more normal of the two. Wake changes his disposition on a dime, contradicts himself, and bathes himself in the lighthouse’s light while naked. When a storm prevents the two from getting picked up at the end of their stay, tensions really begin to boil.

All in all, what the film lacks in plot it makes up for as a fascinating character study. It would be easy to assume that the two keepers are constantly at each other’s throats, but in passing the time they find activities and interests to bond over. That’s not to say that they never wind up at each other’s throats, which they do quite literally on occasion. It greatly helps that two stellar actors bring this bizarre relationship to life. Willem Dafoe imbues Wake with just enough wildness and anger to make him intimidating, without going fully over the top into absolute wackiness. Wake also has a considerate side, which Dafoe imbues with genuine tenderness. On the other side, Pattinson has a passive role for much of the film, as Winslow goes about his duties and mostly takes the abuse from Wake. But when he’s had enough, Pattinson releases a rage that comes straight from the core of his very being. In arguably the best scene in the film, involving a discussion of Wake’s cooking, the two actors cycle through a variety of emotions seamlessly.

In addition to the acting, the directing and cinematography are top notch. Eggers knows how to get performances out of his cast, and uses the isolated locale to full effect. Seriously. It seems like every inch of the small island gets used for some key scene, whether it’s the cramped confines of the quarters the two share, the long, winding staircase up to the lantern room, or the seagull infested lawn outside. The strong site-specific directing goes hand in hand perfectly with Jarin Blaschke’s cinematography, which conveys so much with so little. One shot in particular pans from Winslow, across the lawn, and up the lighthouse, building tension as we get the sense that Wake knows his movements from every spot on the island. Filming in black and white is a bold choice, yet it’s a testament to the film that it feels perfectly natural. Likewise, Mark Korven’s score incorporating the repetition of a foghorn seems like it could get on the nerves, but actually heightens the tension between the two, like the horns from Inception.

The only big issue is in pacing, as the aforementioned exemplary qualities can only do so much to hold up a threadbare plot. While there is a sense that the film is building to something, this is primarily done through atmosphere. There are allusions to H.P. Lovecraft and Herman Melville, which play with the mind and suggest a looming nautical monstrosity. But late in the game, and I mean very late, the story reveals that it ultimately takes its inspiration from a certain Greek myth. This doesn’t really track with the rest of the movie, and arrives as the film begins to start losing steam. But for a tale in which two men spend the entirety of the time on a tiny island, The Lighthouse conveys a surprising amount of horror, comedy, and dreamlike imagery.

Summary

The Lighthouse may not be a film for everyone, but the dynamic between the two central characters, and the actors playing them, provides a fascinating series of scenes. Some scary, some funny, and some that will leave audience members scratching their heads. Regardless of how you feel, you’ll definitely think about how lighthouse keepers really did have to do this job, isolated from society and occasionally with less-than-agreeable companions.

-

The Lighthouse