If you haven’t gotten onto Bandersnatch, then you’re missing a huge phenomenon online. People across the web are playing through the episode over and over, mapping out new pathways, trying to decide if one cereal is more evil than the other, and trying to figure out what endings there are. There are flowcharts and memes aplenty, and theories galore as to what it all means.

But if you’re really digging into the world of Bandersnatch, you might find something surprising. There is no way to “win.” Well, at least not in the way that the episode presents it.

Now, some of the major themes of Bandersnatch are control and free will. Whether we are in control of our own destiny, or even our breakfast choices, or even if there’s such a thing as choice. And while we can debate whether or not a fictional work has anything to say about choice, I don’t think that’s the reason why there’s no “winning” in the episode. The truth is that the framing of the show convinces you that there is one set of parameters that would mean success, but there is no ending that encapsulated all of them.

Here’s how the show frames the plot:

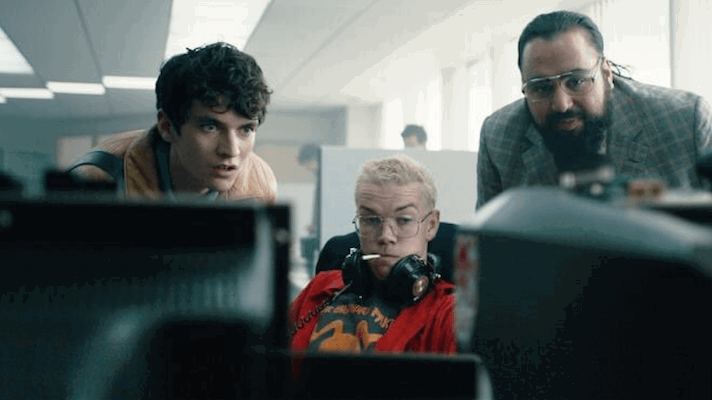

In 1984, Stefan Butler is a young game designer who effectively sells his first game to a big company. However, he only has three months to complete the game, which is based on one of Stefan’s favorite books, a choose-your-own-adventure epic called Bandersnatch. From here, several decisions can be made by the viewer, mainly leading to either Stefan making a terrible to mediocre game (if he stays on his mental health medication especially), or making a groundbreaking masterpiece as he feels his control slipping, but to do, ends up killing his father, losing his mind, and going to jail.

In this scenario, you’ve got three objectives:

- Get a 5/5 score from the TV videogame critic

- Don’t die

- Don’t kill the father (or don’t get caught killing him so you go to jail)

Of course, none of the endings that are achievable meet all these criteria, so a perfect win is not achievable. But can we talk about how weird a premise this whole thing is?

Let me reframe the premise a bit, and let’s see if meeting these criteria seems reasonable:

In 1984, Stefan Butler, an untrained young man, pitches his very first game ever to a big name label that then decides it is a game that can and should be finished in two months. Whenever Stefan makes decision that would endanger his mental health, his game progresses positively, and vice versa. The entire basis on which the success of the video game is assessed is on one critic’s summation on TV, a critic we know is hard because he only gives out 4s to Stefan’s hero, game maker Colin Ritman. The only way to make a perfect Bandersnatch game, i.e. get a 5 from just one critic, is to kill Stefan’s father and dismantle the body as well as forgoing medication.

When you look at it like this, and assume that part of the problem is that Stefan is, indeed, having a breakdown, then the story shifts. No longer is this man versus destiny, it’s man vs. his art. Stefan can either make a perfect game or stay sane…but is that really true?

First of all, Stefan is brand new to professional game design. Like, seriously brand new, selling his very first game. The fact that any company that was responsible and cares about creating a lasting legacy would push a first-time creator to craft a finished product in a few weeks time is ridiculous. Beyond advertising and packaging it, they would never, ever trust that a project like that wouldn’t need editing, reworking, and tweaking.

Second, the score system is the ultimate trick. If you have ever played a game, you know that getting the most points means you win. Therefore, we conclude that get a 5/5 is the best outcome. But this whole thing is a logical fallacy. For one, Colin Ritman’s games, which Stefan is a huge fan of, never got a 5 and they are hugely successful. Literally, Colin made enough money to buy a fancy car and yet, he never got a 5. Second, we are basing the “win” score on one, very harsh critic. As a critic, I know that my opinion on its own well and truly does not matter. My opinion only works when it lives in a cultural conversation. Not to mention, just because I (or any critic) don’t like something, it doesn’t mean that thing is bad or unenjoyable. There are lots of movies, TV shows, and games that were panned by critics that went on to become classics. So the whole scoring system is juvenile and misleading.

But most importantly, Stefan acts like if Bandersnatch is a critical failure, then his life is over. Let me say that again – if his very first game is not an immediate success, then there’s no point but to go back in time and make it again. Creatives all have that project that you pour your heart and soul into, that you work to make great. Often times, that work doesn’t live up to our expectations or the expectations of others and yet, the only way you fail is if you obsess over it and don’t learn from it. Colin Ritman doesn’t take it that hard when his games don’t get the perfect score, he just moves on and tries to make his next games better.

Black Mirror has always been a franchise about how bad decisions and selfish impulses mixed with technology will destroy you. And while the episode also messes with the idea of destiny and multiple universes, on top of the importance (or lack thereof) of choice, it does extrapolate a common myth: creatives who are sick make their best art when they are suffering the most.

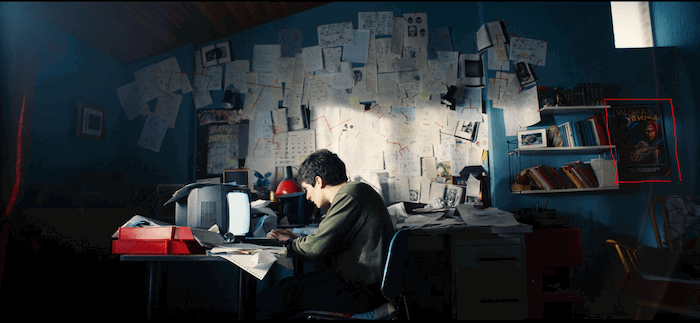

Any choices you make to have Stefan do the thing that would keep him healthy, like working in a professional environment with help, taking his medication, or seeing his therapist, “ruins the game.” And by ruin, we mean get a 0 or a 2.5 from one critic on TV and prompting you to start again. The “true” ending is the one where Stefan kills and dismembers his father’s body, finishes the game, then gets caught and goes to jail. Then, another game developer, Colin’s daughter Pearl begins to remake the game, and the only way the episode can end is with the viewer choosing to stop her, or at least hinder her, by destroying the computer in one of two ways. So what exactly is Bandersnatch trying to tell us?

I think, honestly, it’s about how destructive obsession is. Stefan’s real problems really begin as the deadline draws closer and closer, and he begins to isolate himself even further. He is under so much stress that when his dad finally tries to intervene, he flips out and kills him, before hiding the body. Again, stress about making his very first game ever perfect, like it’s going to be the finished product rather than something that would be heavily edited and worked through. But there’s no reason to be – it is not life or death, but he becomes too fixated on the idea, so entranced with it, that he can think of nothing else, to the point where he feels like he has no choice.

Ultimately, I’m not sure if Bandersnatch is promoting the myth that illness feeds creativity, or if it’s trying to highlight its futility, but I think it is important to get to the meat of the story: in this scenario, there is no winning. You can be a genius and a murderer, or mediocre and sane. But success is not a scorecard, and it’s certainly not based on what you accomplish in your 20s alone. Stefan’s folly in thinking that Bandersnatch will define his entire life, so that it then become a self-fulfilling prophecy. So whatever you choose this year, be it Sugar Puffs or Frosties, make sure you realize that very few things in life have to be one or the other.