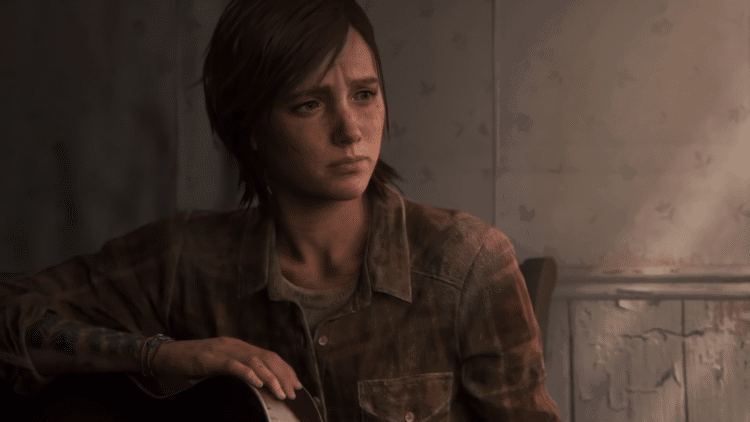

Some games have great endings, and others have endings that leave much to be desired. But what happens when a game has both? I recently finished playing The Last of Us Part II, and for the first time, experienced this bizarre phenomenon of overindulgence. Arriving towards what I believed to be the ending of the game, I felt satisfied with each character’s story seemingly wrapped up. Not only did I feel satisfaction, but also sadness, a sense of relief, and perhaps the most empathy I ever felt in playing a game. At that moment, I understood the motivations of every character, regardless of morality.

I braced myself for the credits to roll, with a sense of acceptance. But they didn’t come. Instead, the game went on for several more hours, which, while providing some fun gameplay, undercut all the powerful feelings, resonances, and messages that the initial faux ending provided. When the game finally did end, it felt disjointed, muddled, and almost comical in its tying up of loose ends to unravel them all wildly. The Last of Us Part II serves up a near-perfect ending and then throws it away.

So how does the game end, and why does it work so well at first and then go awry? Spoilers follow for both The Last of Us and The Last of Us Part II. You’ve been warned.

In The Last of Us, the original game, protagonists Joel and Ellie travel across a post-apocalyptic America to bring Ellie to the Fireflies, a group developing a vaccine against the zombie infection. However, when Joel realizes that the doctors have to kill Ellie to make the vaccine, he massacres everyone at the hospital and leaves with an unconscious Ellie.

The game ends with one of the greatest moments in gaming history, as Joel tells Ellie that they left because the doctors realized they had another way of making a cure. She’s skeptical and asks if this is true, feeling that her purpose was to help provide the cure even if she died. Joel lies again, out of love or selfishness or both, and says they didn’t need her at all. It’s powerful and heartbreaking, as it asks how far someone should go for love, even if it means doing something horrible along the way.

As such, the sequel picks up with the logical implications of this act. Abby, the daughter of a doctor Joel killed, hunts him down and murders him. Ellie pursues her for revenge, killing many of Abby’s friends along the way, before finally confronting her. But just as she confronts Abby, the game goes back and has us play through the same events from Abby’s perspective. Finally, reaching the moment of confrontation, we now have both points of view under our belts. And what comes next is an uneasy boss battle, as we fight Ellie as Abby, and eventually witness the two spare each other. Abby goes with her surrogate son Lev to California, while Ellie departs with her girlfriend, Dina, back to Wyoming.

Months pass, and we see Ellie and Dina with a baby, Jessie’s child, who was previously killed by Abby. They’re a family tinged with loss, constantly aware of it, yet they nevertheless have achieved their dream of running a farm together. Ellie has PTSD, yet Dina comforts her. Tommy, Joel’s brother, shows up and laments Ellie sparing Abby’s life, but Dina defends her. They give up their quest for revenge, and while they bear the severe scars of it, physically and mentally, they have the comfort of a loving family unit. It’s here is where I believed the story would end, with a sense of ambiguity about the future of all the characters, but also a sense of closure, as the characters have learned to live with the joys and disappointments of life. In many ways, it mirrors the bittersweet ending of the original game, as all the primary characters are safe, but at a great emotional cost. Ending right there, it’s one of the greatest video game endings of the past decade, if not all time.

There’s just one problem. It’s not the ending. Instead of the credits, we see Ellie pack a bag and decide to pursue Abby once again. Dina tries to stop her, reminding her that she has a family to think of, but Ellie either doesn’t think of it or doesn’t care. Meanwhile, Abby and Lev find out about a group of Fireflies still holding out, but on the way, they get captured by slavers. Ellie arrives in Santa Barbara and kills the slavers, finding Abby tied up on a pillar about to die. Ellie saves her, and after Abby thanks her, Ellie explains she actually came for another shot at revenge. Abby, incredibly weak, says she won’t fight anymore, but Ellie forces her to by saying she’ll kill Lev if she doesn’t. Just as Ellie is about to kill Abby, she lets her go, once again. Journeying back to Wyoming, she finds Dina and her baby gone, and the game ends. It’s a bizarre and confusing ending that takes a powerful resolution and sucks all the drama out of it, leaving The Last of Us Part II all the weaker for it.

Going into this argument, I want to make a few things clear. I enjoyed The Last of Us, the original, and overall, I enjoyed The Last of Us Part II as well (as we here at The Outerhaven did in our review). I appreciated the risks the sequel took by killing off a beloved character and having players play as the antagonist for the second half of the game. Ultimately I gained sympathy, dare I say empathy, for Abby, the latter character. While I hated her for what she did, I can’t say I didn’t understand why she did it. I also sympathized with Ellie, of course, and understood her fury in reaction to this seemingly unjust crime.

But at the same time, these sentiments are precisely why I have mixed feelings about the ending, as the story built to something near perfect and then decided to undercut it. To be clear, I’m not decrying the ending because the characters did things I didn’t want them to do. Rather, I’m arguing that whatever message the game aimed to convey about its characters did not do so effectively. Let’s get into why the faux ending, or farmhouse ending, is so powerful and why the true ending or Santa Barbara ending, waters it down.

With the farmhouse ending, we see what the characters these things on the hierarchy of needs. Ellie values revenge for Joel, but not more than her love for Dina, as she specifically has Abby spare Dina’s life in exchange for giving up her revenge quest. Ending the game here sends the message of what people will do for love, just as the first game does. But when Ellie goes back on this deal, the implication is that she doesn’t really care about Dina, or rather no more than seeing Abby dead. As such, when she realizes Dina left her, there isn’t much of an impact. Dina didn’t leave her so much as she left Dina. So perhaps she values revenge more than love, and yet, she doesn’t even kill Abby. So we don’t know what Ellie values at all. This ending isn’t ambiguous. In fact, it’s confusing.

Now, there is a small yet crucial detail to Abby and Ellie’s first fight: Abby gains the upper hand, leaving Ellie, Dina, and Tommy licking their wounds. Yet, Abby is just as battered, and Ellie could have easily shot her in the back if she wanted to. So Ellie still spares Abby’s life; it just comes down to a code of honor. Ellie gives up in exchange for Dina’s life and backs down. Therefore, her second shot at revenge seems more motivated by pride. Without Dina, Ellie doesn’t have to bargain. She wouldn’t shoot Abby in the back because that’s not honorable. We know this because she deliberately saves her from the slavers to “challenge” her to a fight. When she wins, she then backs off, and this time the humiliated Abby walks away from taking a cheap shot at Ellie.

While this chivalrous code of conduct makes for riveting drama in Hamilton the musical, with characters killing each other through stringent dueling etiquette, it doesn’t make much sense in a video game about the apocalypse. Further undercutting this weird code of honor is that several revenge killings don’t abide by it. Joel, Jesse, and Abby’s friends never get fair chances to defend themselves. So for all intents and purposes, the second ending of The Last of Us Part II is about Ellie seeking a slightly less humiliating outcome. But if it ended at the farmhouse, the game’s notion of acceptance in the face of humiliation would have fueled a more poignant ending about letting go.

So how does the game try to justify that Ellie has to seek revenge once again? The primary impetus is that after leaving Abby alone, Ellie is still haunted by the death of Joel. She suddenly decides that only killing Abby once and for all will end her PTSD. There are several things wrong with this. One, I’m no psychologist, but I’m pretty sure that’s not how PTSD works. If PTSD were ended only by someone killing the person who caused the inciting incident, then there would be many more murders and a lot less trauma in the world. Including a character with PTSD is a good representation, which holds up in the farmhouse ending, but suggesting that it can be cured through murder is less than exemplary storytelling.

Ellie doesn’t kill Abby, and it seems that letting her go is actually what improves her mental health. This is… still not how mental illness works, but it’s at least more of a positive message. The problem is, she already let Abby go free. When she frees her from the pillar, she does it again. And when she lets her go from the water, she does it again, which perhaps counts. Why this time? Why is it different? Will she try to kill Abby again? Will Abby try to kill her again? When does it all end? Instead of contemplative questions about the effects of trauma, the second ending leaves us with less profound logistical questions.

Ultimately whether Ellie kills Abby or not is immaterial. The important thing is that she either does it or doesn’t do it and grows from that as a character. Instead, Ellie tries to kill Abby, gives up, and then tries again, and then gives up again. In the legendary words of Star Wars’ Yoda, “Do or do not, there is no try.” To have her decide not to do it in the first place is interesting. To have her make the same choice repeatedly is just tedious.

With the initial farmhouse ending, the message of The Last of Us Part II appears to be, “If you go looking for revenge, dig two graves.” A poignant moral about the futility of revenge and how it causes more harm than good. Sure, Ellie and Abby, each have families of a kind at the end, but they’ve had to bury a lot of people along the way. With the prolonged Santa Barbara ending, the message becomes, “If you go looking for revenge, and at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. And then maybe give up eventually.” It’s an adage that’s just as sloppy to say as it is to enact. The original game makes you wonder about the lengths you’d go to save a loved one, while the sequel ultimately makes you wonder why the game wasn’t just a few hours shorter.