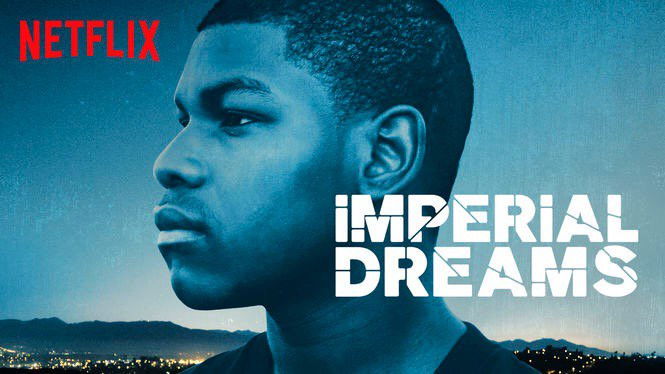

The plot of Imperial Dreams is centered around Bambi’s attempts to break free from the pervasive violence in his L.A. neighborhood, all in a bid to give his young son Daytone a better life. He faces racial profiling from the police as well as pushback from family when he tries to break free from his past. Themes of mass incarceration and privilege are both explored, giving us a nuanced glimpse into his life after prison. Both themes strike home in an increasingly divided United States, where not all opportunities are created equal. It’s timely and relevant, particularly as politicians debate how to improve our justice system.

The U.S. possesses the highest incarceration rate in the world at 724 people per 100,000. This is in part due to the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. The act mandated life sentences for criminals convicted of violent felonies after two or more prior convictions, and this included drug crimes. Also provided were $8.7 billion in incentives for state governments to build prisons, provided they increase the harshness of their sentencing via ‘truth-in-sentencing’ laws.

The obstacles Bambi faces as a result of his prior felony are nearly insurmountable. It’s clear in the film that he views his past choices as mistakes that were harsh realities of the life he was born into. Opponents of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act believe that incentivizing harsher sentencing disproportionately affects low-income neighborhoods like the one Bambi grows up in. In 2015, former-President Clinton said of the crime bill, “The good news is, we had the biggest drop in crime in history. The bad news is we had a lot people who were locked up, who were minor actors, for way too long.”

Bambi’s uncle calls the shots in their Watts, Los Angeles neighborhood. Working for him offers the promise of steady and considerable cash, and Bambi wrestles with his conscience and responsibility to his son Daytone. Bambi simply can’t afford to go back to prison and yearns to make his way as a poet. He struggles to find work as a felon and doesn’t have a license. He can’t get a license because the state filed a child support claim when his son’s mother was incarcerated, and he can’t pay that child support without work.

A New York Times op-ed titled “Why Mass Incarceration Doesn’t Pay” highlights this hardship:

“A criminal record creates substantial obstacles to employment that could increase with the amount of time served, and incarceration decreases earnings by 10 to 40 percent, compared with similar workers. The fact that so many states have rules (including unnecessary and unnecessarily inflexible occupational licensing restrictions), and companies have practices that make it harder to hire former prisoners compound the economic and human damage.”

Bambi’s predicament is an all-too familiar story for many in a time when we need federal sentencing reform. It’s an impossible situation that pushes the ‘American Dream’ further from his grasp. Desperation forces good people to make difficult choices that might just mean losing their freedom in the process.

Ultimately, Bambi manages to rise above his circumstance through hard work and pain, but not without severe consequences. I won’t spoil the ending but suffice it to say it’s bittersweet. Great films aren’t only well-crafted or acted. They facilitate difficult discussions and teach us increased empathy along the way. Imperial Dreams ultimately raises the question: how does our society expect anyone to improve themselves without a fair opportunity to do so?